By Simon Firth, May 2006

It’s that big scratch across Scarlett O’Hara’s

face, the red blur obscuring Robin Hood’s heroics,

or the white blotches that pepper King Kong as he climbs

the Empire State Building.

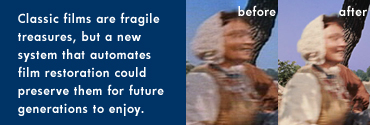

Classic movies are fragile treasures. They pick up dust,

are easily scratched, and often shrink or fade and get

otherwise disfigured as they age.

The most famous will occasionally be painstakingly restored

by hand, says HP Labs’ Qian Lin. But of the thousands

of other movies sitting in archives around the world, Lin

says, “very few go through this manual processing,

because the cost is very, very high.”

That’s a big deal to Hollywood studios like Warner

Bros., owners of Gone With the Wind, Robin Hood, King Kong and thousands of other classic features.

HP researchers, in collaboration with Warner Bros. Motion

Picture Imaging, have come up with a process for automating

much of the restoration process and are now looking to

bundle their set of media-processing techniques into a

single engine, or video-processing pipeline. It’s

already yielding some spectacular results.

In test clips Scarlett now sweeps down the stairs to meet

Rhett unaccompanied by background glitches; Robin Hood

fights his battles in glorious, sharp Technicolor; and

King Kong climbs through a clear Manhattan sky.

“We have many of the most beloved and important

films ever made in our library, and we feel a strong responsibility

to preserve these films so that future generations will

be able to enjoy them,” says Chuck Dages, executive

vice president of Emerging Technology at Warner Bros. “And

from a pure business standpoint, these films are an invaluable

asset and need to be properly cared for."

Studios need to re-copy their movies every time a new

distribution technology comes along, says Dages.

Following VHS video and then DVD, the industry is now

moving toward the next generation of optical disc formats:

High Definition DVD (HD-DVD) and Blu Ray formats. The new

formats offer studios a great economic opportunity, Dages

says, but a challenge too.

“Older movies that have been transferred to video,” he

explains, “just don’t cut it when they go to

the high-definition television formats”

In response, studios are making super-high resolution

digital transfers of each frame of many of their library

movies. But without special processing, whatever dirt,

scratches or other imperfections that mar the original

frames are transferred to the digital copies; all in high

definition.

Until now the only way to get rid of imperfections, explains

Dages, was to have “someone sit with a mouse and

laboriously click to take the dirt out.” No wonder,

he says, Warner Bros. was hoping “that there was

HP technology that could be applied to help automate the

process.”

Although HP Labs had never looked at film restoration,

researchers had plenty of experience working with still

photography and personal video.

“We found that a lot of that expertise can be applied

to the film restoration process,” says Lin, who leads

the research team.

Researchers were able to apply much of what they'd learned

from an earlier investigation of color-sensor technology

to address blurring of images in older color library titles.

Work on single- lens cameras that de-blurred an area of

color using edge information from other patches of color

in the frame also proved useful, as did research into video

super-resolution, a technique for combining information

from nearby frames to increase a particular frame’s

resolution.

The automated restoration process works like this: Each

film clip is first run through a set of algorithms that

selects out only the frames likely to contain an image

artifact. For example, says researcher Amnon Silverstein, “we

look for a pixel that changes color dramatically from frame

to frame. Or within a frame we look for a small area that

is very different from everything else in its neighborhood.

And in color, we look for things that are saturated and

unique.”

A second pass fixes many of the glitches. When dust creates

a bright red, green or blue spot in the frame, for instance,

the researchers' software fills it in with information

interpolated from the area around it.

Although some particularly complicated frames must still

be repaired by hand, automated fixes dramatically reduce

the amount of manual work required.

In the cases where the team had access to scans of the

original set of color negatives, the images took on a new

life.

“Thanks to this technique, you can now look at the

chain link in Robin Hood’s armor or the lace in Scarlett

O’Hara’s dress and they pop out with incredible

detail and a purity of image that you never saw before,” says

Richard Place, global manager for all of HP’s Time-Warner

accounts.

Digitized frames from black and white movies, for example,

contain less information, making scratches, dust and other

errors harder to spot. Early black and white film also

tends to look grainy and suffer from flicker, a result

of the poor shutter control on early cameras, giving each

frame a different exposure.

Perhaps the team’s biggest challenge was Cinerama.

Only 13 features were made using this widescreen technique – a

format that requires a cinema equipped with a curved screen

and three projectors that run simultaneously – but

nearly all are considered classics.

The HP team worked on clips from the 1962 epic, How the

West Was Won. Beyond the usual dirt and scratches, Cinerama

films doubly distort when transferred to home-viewing formats.

Because they were projected onto a curved screen, they

look odd when shown on a flat screen. And they suffer from

clear overlaps and lines where the three images join.

“To resolve the vertical-line issue, the team borrowed

technology for putting ink on paper, which is very similar

to putting ink on film,” reports Richard Place. “They

then used another algorithm to eliminate the flattening

distortion.”

The result, says Warner Bros. executive Dages, “is

remarkable. The technology really has turned what has been

an issue for many, many years into a solution that allows

us to repurpose the film.”

HP and Warner Bros. Motion Picture Imaging envision a process that would

either run automatically or be ‘dialed’ up or down in sensitivity

depending on what is happening in a particular sequence (the more action,

the more likely that one of flying arrows, for example, might be mistaken

for a scratch, requiring the software’s sensitivity to be turned

up).

Cleaning entire films requires enormous computing resources.

“These films take up terabytes of storage,” says

researcher Silverstein. “So we’ve been looking

at how you can take a film, send it out across a set of

servers, process it efficiently, and handle cases when

machines are added and removed.”

Each two-hour movie has 172,800 frames – if you're

processing that on a single machine at about five minutes

per frame, it would take 600 days to complete an entire

movie. By using a cluster of servers, engineers can speed

up the process considerably.

Such a process would employ state-of-the-art data security

from HP, a crucial feature for content owners worried about

video piracy.

It’s not just Hollywood that could benefit from the innovations

behind the video-processing pipeline.

There are major theatrical movie archives in India and

Hong Kong, for example, as well as large research holdings

in public collections like the U.S. Library of Congress.

Although digital is gaining ground, film remains the medium

of choice for making movies and high-profile television

dramas.

And despite its flaws, says Warner Bros.' Dages, film

continues to be the studio’s preferred archival material. “We

know,” he says, “we can put a piece of film

in the vault and under proper conditions, it will last

up to 600 years. It is a great archival media."

Simon Firth is a writer and television producer living in Silicon

Valley.

|