RDF is considerably biased in favour of the data producer. Consumers may have to deal with all, some, or none of the expected properties or classes, and be aware that entirely unknown properties and classes are entirely possible and legitimate. This is one application's attempt to deal with all that is thrown at it.

<House rdf:resource="http://example.com/damian_house"> <address parseType="resource"> <number>137</number> <street>Cranbook Road</street> <city>Bristol</city> </address> <resident> <Person rdf:resource="http://example.com/damian"> <name>Damian Steer</name> <mailbox rdf:resource="mailto:damian@example.com"/> <rdfs:seeAlso rdf:resource="http://example.com/document_b.rdf"/> </Person> </resident> </House>

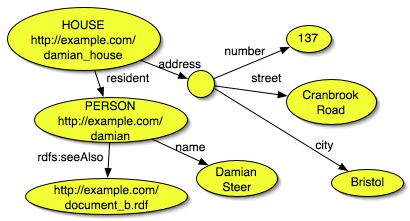

The graph looks a little like this:

Imagine you had to present that information. What would it look like

ideally? My suggestion is that you'd see that there was a house, with

address 137 Cranbrook Road, etc. and that resident at this house was

person "Damian Steer" who had an email address

damian@example.com. That is there are two things: a house

and a person, and they are related. This should be obvious to the

user.

Perhaps an obvious route to follow is using existing XML styling mechanisms to achieve this ideal. (HyperDAML uses such an approach, for example). However the XML approach is at the mercy of the form of the RDF serialisation. Although my example is quite readable the same information could be given in a form three times longer with data about the house and the person intermingled.

An RDF approach must be better. But this presents problems as well. Here are two approaches:

So how to can an application find the obvious patterns in RDF data? RDF, unlike XML, has no mechanisms for expressing data structure; indeed, it is a semi-structured data format so such information would only be a partial help. Having said that the reader may be aware of RDF schemas. Don't be fooled by the name: RDF schemas describe properties and classes, but can't state 'Houses have addresses'. (Closer to this ideal is schemarama).

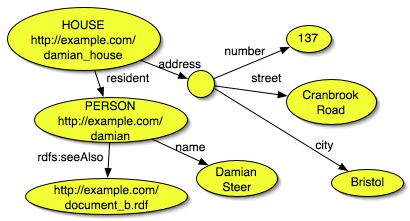

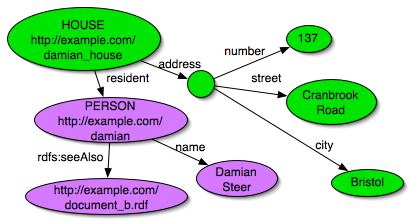

But when one looks at rdf data it is apparent that there are regular patterns. These are captured in BrownSauce using a simple rule: start at a node and work outward, passing over blank nodes.

In our example this results in a house, with an address, and a resident. But it stops at the resident. If we want information about the resident we find a person, with a name, who is a resident of a house. Success.

House (http://example.com/damian_house) address: number: 137 street: Cranbrook Road city: Bristol resident: http://example.com/damian Person (http://example.com/damian) name: Damian Steer mailbox: damian@example.com seeAlso: http://example.com/document_b.rdfOr, graphically, our original graph is divided into two regions relating to the house and person:

I confess my example was rigged. But using genuine data, gathered

from the wild (i.e. the web) shows some success. The reason for this, I

suspect, is that slapping global identifiers on nodes which only appear

for structuring purposes is a little pointless. For example collections

are often blank, such as the rdf:Seq nodes in RSS 1.0

feeds. I think it's doubtful that people would want to refer to the

collection in a feed rather than the feed itself.

BrownSauce is essentially producing a subgraph of the original data, one which (hopefully) contains all the information pertinent to the subject. This subgraph has another useful property: the leaf nodes are all identifiable (i.e. not blank) so linking is robust.

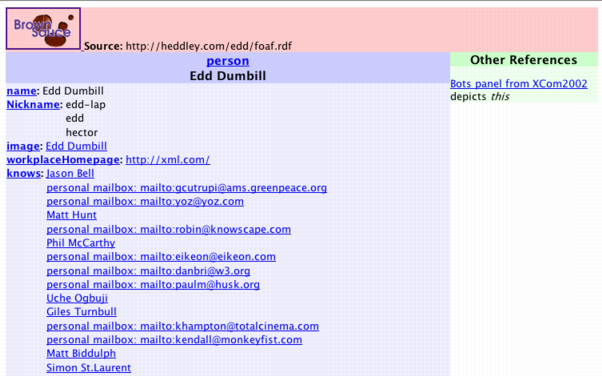

Having said this the original rule often failed on one particular type of data: FOAF data. Here is an example of just such a failure:

<foaf:Person> <foaf:mbox rdf:resource="mailto:a@example.com"/> <foaf:knows> <foaf:Person> <foaf:mbox rdf:resource="mailto:b@example.com"/> </foaf:Person> </foaf:knows> </foaf:Person>

The problem is that the coarse graining results in only one person,

not two. This coarse graining misses out some information: that the FOAF

people are, in effect, labelled. foaf:mbox is a

daml:UnambiguousProperty, that is a property whose object

uniquely identifies the subject. This information is contained

in the FOAF schema. (Edd

Dumbill has

provided an good introduction to FOAF, and I should add such

semantics are not part of RDF proper, but FOAF's use is not unique).

As a consequence BrownSauce coarse grains by traversing until it reaches an identifiable node: that is, either a node labelled with a resource, or the subject of an unambiguous property, or a literal. And to do this BrownSauce loads all schemas it encounters (which I believe is fairly unusual in RDF applications).

This also means that the subgraph BrownSauce produces is not quite what might be expected. The house subgraph is actually identical with the graphs above, but the person node is marked as a boundary: i.e. it contains nodes beyond the person node. BrownSauce has to do this to check for other identifiers for the node. It is also useful since the graph contains more information about the boundary nodes, which can help when rendering.

It is the nature of such algorithms to be imperfect. There will

always be some niggling cases, cases where the result simply looks

wrong. For these occasions BrownSauce provides a little customisation:

brownsauce:Traversable. Instances of this class are

unconditionally traversed. For example I happen to like my rss channels

complete, but rss:Item nodes are normally labelled. RSS

channels then become largely lists of references to items. However by

adding rss:Item rdfs:subClassOf brownsauce:Traversable to

the customisation file custom.rdf all items are traversed

and the full feed results.

Although I've concentrated on the coarse graining feature here BrownSauce has some other features worth mentioning.

In an ideal world we would never see a URI in browsers, and that

includes BrownSauce. To this end BrownSauce treats

rdfs:label (unsurprisingly) as a label for nodes. For

example if a model contains a statement http://example.com/blah

rdfs:label "Blah" then the front end shows "Blah" rather than the

URI. But since labels aren't that common outside schema documents

BrownSauce also treats properties as labels if they are subproperties of

rdfs:label. This might be from the schema itself, or in the

custom.rdf file. For example custom.rdf contains the

statement foaf:name rdfs:subPropertyOf rdfs:label, and as a

result some of the people in the above screenshot have been displayed by

name rather than some obscure alpha numeric sequence. Property and class

labels are also used (if the schema is available) in preference to the

local name.

BrownSauce also keeps track of rdfs:seeAlso links. In

the original release these were simply used as links to other rdf

sources, but now data can be merged from multiple sources. So if a

document contains little information about a thing, but points to more

information, this can be added.

One feature of this would be typed seeAlsos. Suppose that you know a

book has an entry in a database with a Squish/SOAP endpoint. In your

bibliography you might add: <some_book_id> rdfs:seeAlso

<database_endpoint>, <database_endpoint> rdf:type

<squish_soap_class>. BrownSauce could then add data from

that source using the appropriate backend.